In an evening of political shuffles from newly appointed UK Prime Minister Liz Truss, one ministry that would retain a degree of stability otherwise eschewed by the country’s recent political past possibly breathed a sigh of relief as news emerged on 6 September that Ben Wallace would be staying on as Secretary of State for Defence.

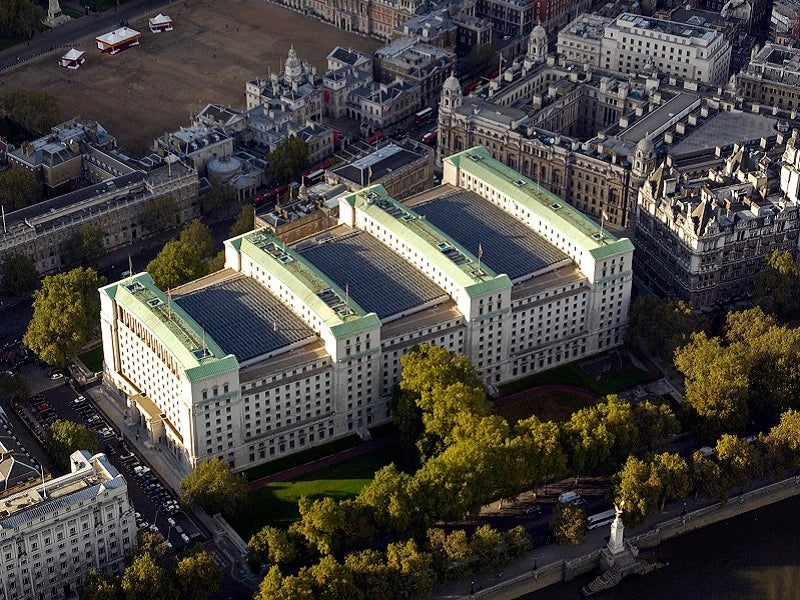

Political footsteps have changed often in the corridors of power inside Main Building, but Wallace has negotiated the Conservative leadership race with a degree of élan. Opting to not put himself forward for the top job, Wallace positioned himself as a continuity minister, the individual with a tight grip on the portfolio at a time when war in Ukraine looks certain to run for months, even years, to come.

Wallace stayed quiet as cabinet ministers threw their weight behind the rival bids of Truss and former Chancellor Rishi Sunak. Crucially, Wallace was one of the last to pick a side, waiting until 28 July before going public in backing Truss.

But what of the position itself? Time was that the UK Secretary of State for Defence was a political heavyweight, considered to be one of the great positions of state along with those of Number 11 and the Home Office.

The BBC cast an unintended stone at the creaking panes of the Ministry of Defence (MoD) reporting that no “white man” was appointed to one of the “great offices of state” in the new Truss cabinet.

However, given the worsening security situation in Europe, as well as developments in the Indo-Pacific, defence has been thrust to the fore. Although the interventionist wars in Iraq and Afghanistan had a significant impact on defence, there was not the Cold War-style threat that the UK looks to be facing today.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataThe political landscape has changed, with MPs rallying around metaphorical banners calling for continued support for Ukraine. Prior to being appointed Prime Minister, Truss had called for the defence budget to increase to 3% of GDP, up from around 2.2% currently, by 2030.

An affordable budget?

Malcolm Chalmers, deputy director general at the Royal United Service Institute (RUSI) think tank, writing in an analysis paper published on 2 September, said that while a defence budget boost to 3% of GDP would serve to boost the UK’s military capabilities, there had been little discussion as to how it would be financed.

According to Chalmers, to reach 3% of GDP for defence, the Truss government would need to increase spending by about 60% in real terms, which would be equivalent to around £157bn ($179bn) in additional spending over the next eight years. By comparison, Chalmers continued, the 2020 Spending Review, and the associated Integrated Review, allocated an extra £16.5bn over four years.

“This would be the biggest increase since the early 1950s, when concern that the Korean War might escalate to a wider war with the Soviet Union led to UK defence spending increasing from 6.6% of GDP in 1950 to 9.6% in 1952, before falling back to 5.9% by 1960,” Chalmers detailed.

Continuing, Chalmers said that the first indication as to whether the new government was “serious” about the 3% target would come in the next Spending Review, which is likely to take place in November this year.

“For the 3% commitment to be credible, the Ministry of Defence would expect to be compensated for the extra inflation since the 2021 Spending Review, and for planned real-terms cuts in the resource budget for the next two years to be reversed. To ensure that the 60% increase in real-terms spending leads to a commensurate rise in military capability – and is not eaten up by increased inefficiencies – careful planning and preparation will be essential,” Chalmers explained.

To this end, significant investment in defence industrial infrastructure would have to be committed to as well as increasing a larger service personnel workforce. The defence estate itself would also have to be considered, to accommodate an increase in regular personnel, thought likely to be around 190,000 by 2030, up from 148,000 at present.

“Given the immediate capacity constraints, the pace of spending growth is likely to be slower in the early years, before accelerating towards 2030. This could mean that defence spending rises from 2.2% of GDP in 2022/23 to 2.5% in 2026/27, before increasing to a full 3% over the following four years,” Chalmers said.

Quite how a country on the verge of recession and experiencing inflation of 10.1% will be able to achieve these targets is unknown. The public purse is still reeling from the Covid-19 pandemic and other government departments, such as health, remain immense spenders of public money.

Spending priorities

According to UK public spending statistics published on 19 May this year, the total Departmental Expenditure Limits (DEL) from 2020-2021 saw £193bn spent on health and social care and nearly $73bn on education. Defence was only fifth highest in terms of DEL at $42.35bn, behind Scotland (£44.08bn) and business, energy, and industrial strategy (£44.67bn).

“If the government is to raise defence spending to 3% of GDP, it will need to argue the case for doing so in the context of wider fiscal priorities. In contrast to the funding of spending increases for the NHS and social care under the last government, there has been very little attempt to ready the British public for the sacrifices that will be needed for a similar level of increase for defence,” stated Chalmers.

Despite his success so far, and trust placed by Truss, Wallace will have a considerable set of challenges piling up, from Royal Air Force recruitment scandals, delayed programmes, and training shortfalls. The challenge has probably only just begun.